Guest Blog: Dr David Slavin, Occupational Health Physician

Public safety is the number one consideration during the Coronavirus pandemic, closely followed by when we will emerge from lockdown, return to the workplace and resume economic activity. This significant step forward in helping organisations get back to work safely is currently underway, as this week the UK Government privately shared draft guidelines with industry and trade union leaders. This is ahead of the latest review of lockdown restrictions due to be announced on Sunday.

As an occupational physician dealing with high-risk environments, ensuring people are safe at work is not without its challenges. There are, however, risk management approaches, tools, existing expertise, skills and resources to assist those who are planning the post-COVID-19 return to work. This will simply become another hazard in the workplace that can be managed using risk management principles.

Currently organisational risk managers, or those with risk management responsibility, have the task of advising and recommending to their leadership how to restart their organisational operations out of remote or ‘pause’ mode. This is a major stage in any crisis management plan, and it involves an intricate web of business considerations and decisions that examine the areas of workplace risk the pandemic has presented them with.

To effect purposeful and robust decision-making, a three-step approach should be taken:

- Hazards: Risk analysis activity to define what hazards to consider

- Balance of risk: Determine the balance between those identified risks and potential mitigation to put in place

- Implementation: Define outline plans, parameters, protocols and policies to achieve desired safety and productivity outcomes

At the most fundamental level within this process, risk managers and leaders must identify the types of risks and priority considerations as they transition from remote or ‘pause’ mode to the ‘new normal’.

Business imperative risk:

- What is the main business effort? The principal reasons employees need to return to preserve the business. This is a Justification and Optimisation step in Health and Safety law.

- In what order should they return? On-site roles that are business critical.

Business operations risk:

- What changes need to be made to facilitate this? Layout changes, business practice, policies and procedures to be implemented, such as PPE and ventilation. Time, distance and shielding together with new ways of operation have been standard ways of managing workplace risks for many years.

Personal risk:

- How do employees personally feel about returning to work? How do customers feel? Which are most at risk: which category of worker (and clients on the transport system) should be placed in what type of work?

The principles to support navigating this web, aid better decision-making and confirm the best decisions are made in the face of uncertainty are a ‘Tolerability of Risk’ (TOR) approach. This TOR principle has been a cornerstone of UK hazard acceptance for decades. For non-risk managers, this approach accepts certain risks to secure certain benefits, whilst ensuring that any mitigation is commensurate with those risks. In other words, to keep the risks as low as possible.

However, this approach is not straightforward: the uncertainty regarding COVID-19 is great. More testing data with complex advice is not necessarily helping organisations make decisions to restore business. There are also risk perception problems associated with COVID-19, and leaders are faced with classic decision-making problems: taking action versus taking no action.

Unprecedented situation?

COVID-19 is indeed unprecedented, but parallels to the ‘new normal’ situation can be drawn from past experience and established sectors operating in a hazardous, and often highly regulated, public safety framework with proven operating rules. These should be examined for what could be applied in a post-COVID-19 workplace.

AIDS. As a young doctor, I remember the emergence of AIDS before the world knew what it was and how it spread. After the initial public panic and once more was known, ways of safely living with the virus and mitigating the risk of spread via protocols became the new normal: use of gloves during blood procedures by medics, social habits, and use of condoms. We adapted and created a safe system of practice.

The nuclear industry: Similar to a virus, radiation is an unseen hazard, and is more concentrated in areas where the risks are higher. A combination of specialist personnel selection and training for those in hazardous areas, use of ‘safe rooms’, and appropriate PPE ensure the balance of risk is appropriate. We developed a safe system of practice.

The asbestos problem: There is a public safety problem lurking in buildings built from the late 1800s to just before asbestos was banned in construction in 1985. This issue regularly surfaces with demolitions and renovations. Specially trained personnel and PPE is used to remove it safely. We evolved a safe system of practice.

In all three examples, public safety is further augmented by appropriate, professional, accredited best practice, guidelines and legislation.

Risk perception

The typical and expected challenge with a situation transitioning firstly to a ‘safe’ then to a ‘how safe is safe enough’ position is the potential for criticism and loss of trust. In the case of COVID-19, you can have the best return-to-work plan in place, making it as safe as you can. However, those who will make the plan work, the public, will have a different perception of the risks.

Data and information gathering, information and understanding employee attitudes and circumstances is extremely important in helping both build trust and make decisions that involve risk and risk perception. The other significant factor impacting this are regulatory obligations, often based on public risk perception: this also elevates the public’s attention to, and understanding of, the risks.

The analysis of all data, information and attitudes should be deliberately simple and broad, because speed, simplicity and repeatability will be more useful and influential than complexity. This is especially important as we live in an internet-driven world where the speed and spread of information can potentially derail the most well thought-out and robust plans, because non-experts and speculators have filled in an anxious public seeking information.

Risk perception heuristics are another element that can have a significant bearing on how much an individual may trust any plans put in place. 1997, Nach: Renn/Zwick highlights this qualitative characteristic and how it amplifies perception of risk. Of particular relevance to the COVID-19 return-to-work plan is the qualitative risk of dread. This amplified perception of risk to the individual is irreversible for dreadful disease or death.

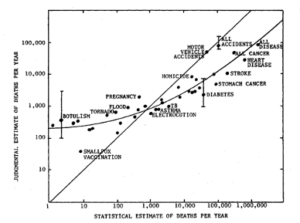

Another important reference in risk perception is the classic Slovic Fischhoff graph which illustrates the gap between public perception of risk (straight line) overlaid with the identified risks (curved).

[Slovic Fischhoff Lichtenstein 1979]

Plans, people and communications

Once a plan is in place and the perception risks are understood, the last element to address is people. Communicating with your main stakeholders is the key to allaying the fears of a nervous public and managing their perception of risk. If you don’t manage the message and communications, you don’t have a stake in shaping the risk perception, reassuring an anxious workforce and building up trust.

Currently we are witnessing a negative public risk perception with the NHS for non-COVID-19 related health issues. A&E departments are quiet, and we have health officials appealing to the public to still come to hospital to be treated for other ailments, such as heart attacks and accidents.

Evidence resistance is also another factor to be mindful of. This is the tipping point, when the public become resistant to evidence and facts that support the plan. Clear, factual messaging around the workplace measures taken is best supported by evidence and facts: your communications department must be involved in its development and curation, with all evidence and relevant facts shared. Once again, data and information gathering will assist with this.

Comprehensive and compliant plans adopting the most robust risk management approach, reviewing existing comparable sectors and case studies are the best approach to making the workplace safe post COVID-19. The next stage is implementation: engaging with your workforce and getting your communications right is key, otherwise people simply won’t want to return to work.

About Dr David Slavin

Dr David Slavin is a specialist occupational physician and business consultant. A former Royal Navy doctor specialising in Nuclear Health Physics, David was Deputy Chairman of the UK military nuclear regulator. After a US Navy Exchange, David joined Pfizer’s Clinical Technology Department, originally to explore risk perception and to develop new risk analysis tools, later becoming Executive Director and Head of the Business Innovation Unit, Pfizer Global Research and Development.

David has spent time as a visiting professor at Imperial College London, one of the few medical doctors to be a professor in an engineering faculty. He is a former member of a Royal Society steering committee and advisor to the UK Government on science and technology on nano particles and risk. He has presented to the US National Academies of Science, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory and a Defense Congressional Committee. He has also presented at the Cheltenham Science Festival.

David is Managing Director of Ocean Occupational Health Ltd., which provides occupational medicine advice and niche science, business and human factors solutions. David is also joint author of The Tolerability of Risk.

“The Tolerability of Risk”: https://www.routledge.com/The-Tolerability-of-Risk-A-New-Framework-for-Risk-Management-1st-Edition/Bouder-Slavin-Lofstedt/p/book/9781844076093

References and further reading:

“Risiko- und Technikakzeptanz (Konzept Nachhaltigkeit) “ (German Edition) 1997, Ortwin Renn, Michael M. Zwick

Further Reading in English: “ Perception and Evaluation of Risks: Findings of the “Baden-Württemberg Risk Survey” 2001

https://elib.uni-stuttgart.de/bitstream/11682/8701/1/ab2031.pdf

“Perceived Risk: Psychological Factors and Social Implications”. Paul Slovic, Baruch Fischhoff and Sarah Lichtenstein, 1979: